Nine Tips to Bridge the Cybernetic Design Gap

By Raymond Kent, Assoc. AIA, LEED AP BD+C, CTS

Director of the Innovative Technology Design Group

DLR Group | Westlake Reed Leskosky

Before you commit to incorporating augmented or virtual reality into your design process, consider these scenarios that could harm, rather than help, your final outcome.

Much like Doctor Who’s TARDIS, the toolbox for design just got a lot bigger on the inside. What was once relegated to testing labs, tinkerer’s garages, and a relatively small segment of the gaming industry has now exploded onto the landscape of everyday tech with the promise to change practice in everything from product design to education to entertainment to architectural design. Unlike other technologies we have seen, augmented and virtual reality are looking to have staying power in a truly disruptive way.

A quick primer on this technology and its current capabilities:

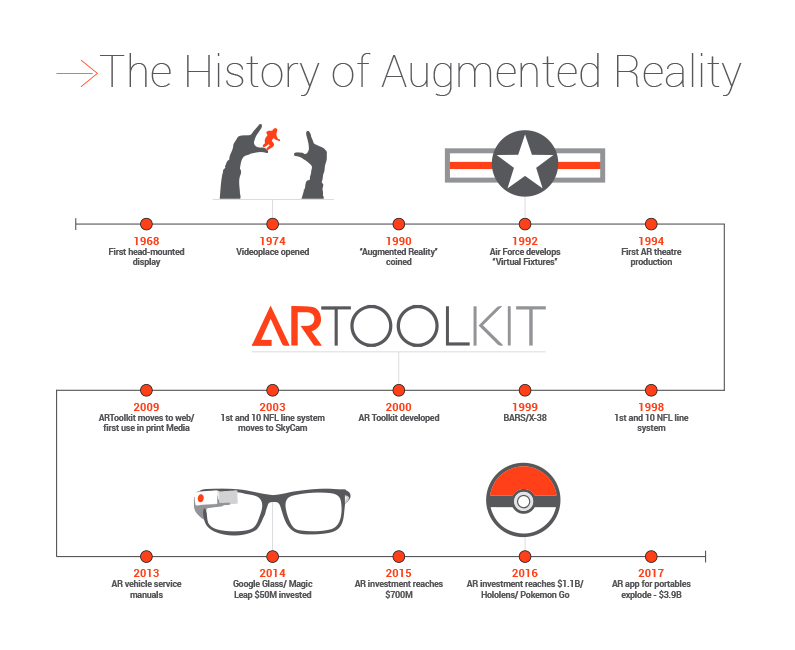

Augmented reality (AR) is a live, direct or indirect view of a physical, real-world environment whose elements are supplemented by computer-generated sensory input such as sound, video, graphics, or GPS data. The most recent successful AR example is a

little game you may have heard of: Pokemón GO. Thanks to the app, millions of users were chasing virtual creatures around the actual globe using their smart phones.

The app generated millions of dollars in sellable data for the game’s creator, and launched AR technology into the mainstream.

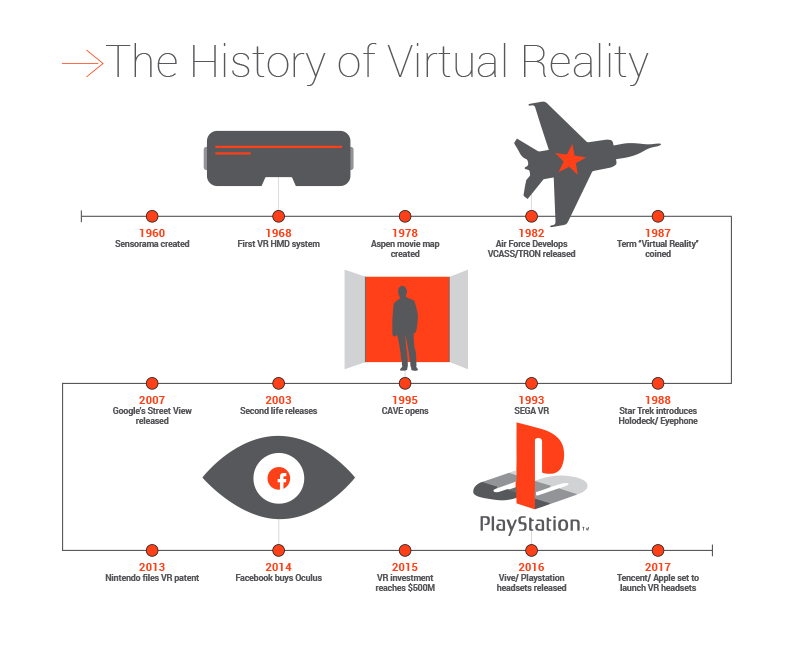

Virtual reality (VR), unlike augmented reality, currently relies on a head-mounted display (HMD) that blocks out all external visual and auditory stimulus and provides a computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional image or environment with which users interact using special electronic equipment. Having the largest presence in gaming/entertainment, medical, and military applications, products such as the HTC Vive and Oculus Rift are providing immersive environments that transport the user into the intended scenario.

Both technologies have a long history dating back to the 1960s and, for much of their collective history, were seen as clunky and expensive. Over the last several years however, investments from deep-pocketed sources coupled with advancements in computing

power and the rise of smart devices, have gotten us much closer to the kind of technology we associate with legendary science fiction lore.

Designing with the Tech of the Future

As designers we have the opportunity to leverage this technology and delve more deeply into the design process in new ways. At DLR Group,

we’re exploring the use this technology as an internal collaborative and iterative process in partnership with our clients, as a part of the product for the client in the form of a marketing/fundraising tool, or as an immersive way to experience

the final environment.

There are a variety of ways to engage in AR/VR and a myriad of price points to go with it, each with advantages and drawbacks. Wading into this world can no doubt be a daunting task for any design team, but enticing possibilities for collaboration and new design techniques far outweigh the hesitancy. Below are some key considerations when deciding to launch an augmented or virtual reality design project.

- Define Your Objectives

There are several key factors to consider outside of which technology to use. In some ways the technology takes a back seat to the actual experience you’re working towards. As powerful as AR/VR technology is, the goal should always tie back to the core mission, brand, or business objective. This drives back to the most basic of questions: Why is using this type of platform necessary, and what do you expect of the outcomes?

If your goal is to have improved coordination between design partners — especially if those partners are off-site — it might make sense to wade into the waters of AR/VR if the project has potentially complicated elements that would benefit from a detailed virtual collaboration. Whenever you’re considering use of these technologies, you should establish a clear value-add to leveraging the technology. - Select the Technology

Once you’ve outlined your objectives, you should review the available technology to consider which one makes the most sense for your project. Does augmented or virtual reality make better sense? Are you using an existing technology you already have? Will it require custom software or off-the-shelf products to allow you to accomplish your goals? These considerations are critical to success as the outcomes may not translate between platforms; content developed for Oculus Rift will not translate to Google Cardboard.Additionally, if your objectives require you to collaborate with partners who may be in a different location, an understanding of their technology will be crucial to them having access to or interpreting and interacting with the information as intended. It would be akin to trying to make a video call to someone who is using a rotary dial phone.

Once you determine what type of experience to use (AR vs. VR) and the type of display technology you need to accomplish it, control of the environment that will host the experience is the next level of consideration. These devices–typically infrared, blue-tooth, or Near Field Communication (NFC) – enable the user to move through the environment, manipulate elements, or call up commands. They can range from gaming controllers, wands, gesture technology (e.g. Microsoft’s Kinect), or even thumb wheels. You should consider who the user is, the environments in which the technology is being used, and what control capabilities exist when deciding which peripheral to choose.

The other side of the equation (and one that often gets overlooked) is the programming side. Often even off-the-shelf software may require some tweaking to get the VR experience exactly how it should be so you and your design partners are successful. Consider the competency of those involved: Does anyone have competency in C++, C#, Java Script, OpenGL, DirectX, Python, Unity, etc.? These are the typical languages used to program AR/VR experiences and are vital to achieving your goal. The programming language used to accomplish this, although important, should allow for the following:- A high consistent framerate

- An experience that does not interfere with the AR/VR experience, often referred to as “breaking presence”

- Deliver an experience designed with spatial AR/VR technology in mind – no 2-D effects, large and out of scale elements, etc.

- Good acoustics and spatial audio in the model so humans orient themselves with sight and sound.

A great resource for AR/VR best practices can be found at dSky:VRFAQ with additional links on this website to Unreal Engine, Oculus, and LeapMotion’s best practice guides.

- Try Before You Buy

First-time users are often awestruck when they initially experience new AR/VR technology. It’s exciting to try new things, but sometimes in their excitement, users lose their ability to deliver actionable contributions or feedback. It’s helpful to schedule training sessions with the team to acclimate everyone on how to best maximize your use of the technology. This could–and often should – include leveraging similar examples or test runs of the current project for your team to try out for themselves before any required constructive meeting. Watching YouTube videos or reading articles about AR/VR – even this one! – cannot replace the sensory experience of the technology.

Using an AR/VR app rather than using expensive computer driven technology like Microsoft’s Hololens or Facebook’s Oculus Rift can simplify this process. That said, understanding the smart device platform is critical. Using or developing a platform specific app can create obstacles, such as creating an app for Apple devices when your partner uses an Android platform, and so you should go into any development fully prepared to create an app that can work across multiple platforms. If you are using an “off the shelf” app, you will need to either work with the developer of the app to make it cross platform, for which there will be a charge and a wait time, or work with your partner to acquire the right platform to use the software. - Understand First-Person Design

In so much as designers think of the collaborative possibilities with this technology, both AR and VR are first and foremost, first-person media formats. Even if everyone is playing the same game, each user sees things from his or her own individual perspective; likewise, because of the iterative and interactive nature of AR/VR, users can contribute to the environment in their own unique way. Think of the deep dive Disney’s research and development teams take into augmented reality to develop future dark rides. Or the fact that Six Flags and Sea World now offer virtual reality experiences in their parks. This technology gives their guests total control over their experience, making it unique each time they visit.The promise of a unique user experience can be highly useful when leveraging AR/VR for use with your client in presentations to the public, or when creating dynamic and interactive content in the final design. This feature is exciting, but it is important to design the framework and boundaries for the environment, rather than have it be endless. If it’s too large, the team gets lost. If it’s too small, you could wind up virtually tripping over each other.

- Separate the Good From the Bad

Investing in quality content will make the experience of designing in AR/VR much more effective, more dynamic, and more memorable. Know your comfort level with creating content, and find the right partner with the right experience to help fill any gaps. Even veterans in the industry have only been around a few years and may not have much to show in terms of number of projects. If you do need this outside expertise, focus on their portfolio but also get a good understanding of how they got there rather than what their final product looks like.

If you are bringing in a partner to assist, it may be worth looking outside your own industry for the expertise for a quality design process and end product.This could include technology specialists from DLR Group’s Innovative Technology Design Group, software and gaming programmers, mechanical and industrial engineers, or interior designers who have the technical and spatial skills required to do the job. AR/VR experiences require writing of code as much as they require good design particularly if a commercially available off-the-shelf product does not exist. The teaming requirements should tie directly back to the original objectives, and how best to achieve them. - Mobile vs. Dedicated Environments

Incorporating a mobile platform for design use requires additional levels of consideration.Mobile app developers will tell you that some of the biggest challenges are creating apps for multiple platforms and multiple versions of operating systems, even on the exact same device. For example, a Samsung Galaxy S8 sold through Verizon is running a slightly different version of the Android operating system than the same phone sold through AT&T, even though they are running the exact same versions.There are essentially two layers to the app design. The first is the actual app design, which considers experience navigation and other out-of-experience control features such as settings. The second is the experience design itself, and how to navigate within the experience. Items such as breadcrumb threads and content libraries often have to be split between AR/VR modes and within the app itself. So the ability to develop or use the tools across both environments to leverage the experience in the design process is imperative. Having controls outside of the AR/VR experience necessary to contribute fluently in the design process will slow down the experience and make it less desirable at tool.

- Duration and Timing of Delivery

Setting realistic expectations for the development, setup, and delivery of the experience so users get the most out of the design process is crucial, particularly if you work on billable time. Even if you clearly define your objectives, select the right technology, and put the right people in place, you can’t completely absolve yourself of delays or complications. A timely approach will allow users to reap the unique, unmatched benefits this technology can produce.Developing the necessary tools to achieve your goals can take an average of 12-to-16 weeks for simple scenarios, and as much as 3-to-6 months before design even begins. The good news is set-up can work in tandem with other initial developmental design processes, such as programming and schematic design, which often mimics the timeframe of AR/VR setup. There are also several shortcuts that can shorten the set-up time, including purchasing stock 3D video capture or computer-generated elements, purchasing pre-written modules of code, or complete software add-ins such as Enscape for Revit.

The duration of design delivery is an important, though often overlooked, contributor to delays. This is particularly true if new partners are brought into a project, or if the design falls short of client expectations. The best way to head this off is by incorporating virtual review points throughout the design process that engage the design team and the client. The more frequently the design team receives feedback, the less likely disruptions will arise. In other words, don’t wait until the end of the design process to deliver the experience to the client. Their reaction may not be what you expect.

- Understand the Technology will Evolve Faster than Your Project

Thanks to large infusions of investment capital being pumped into the market, technology developers are spinning out new technology and software almost daily. This is exciting, but can make for an uneasy landscape. You and your team can chase the proverbial technology tail forever, trying to dazzle and incorporate what new thing just came out. Keep in mind that your main objective is to deliver an experience and a narrative rather than showcase the technology.The AR/VR landscape can be an incredibly powerful design and presentation tool, but it is not a cure-all for unwanted or inadequate design ideas. What it can do is provide solid dimensional collaboration and communication opportunities that present the material in a more intuitive way than 2D drawings or images on a screen. - The Environment for the Environment

The last consideration for using AR/VR in the design process is where you will be using this technology. Mobile applications have the least number of controlled environments and offer the most flexibility, but the output can be affected by the real world environment (e.g. sunlight glare, ambient noise, poor acoustics in the space) that no amount of app development can correct. We should understand these deficiencies and communicate them as possibilities to users.

AR in a dedicated, enclosed, controllable environment requires special consideration to maximize the technology’s ability to display content. For example, acoustics in a dedicated space would ideally provide a reverberation time of 0.7-0.9ms with a Noise Criteria rating of NC25 or better. Surface treatments near any microphone or listening device should maximize speech clarity and intelligibility while minimizing destructive reflections, though this cannot accommodate for human speech defects such as heavy accents, fast talking, quiet talkers, impediments, or slurring. If used, loudspeakers should be placed in a way that allows them to clearly reproduce the spatial audio often used in the environments. This may even require noise cancelling headphones or other listening devices depending on the technology.

Lighting for an AR landscape in an enclosed room using overlay devices, such as Microsoft’s Hololens, requires that lighting be indirect with an even wash (+/- 0,3 FC) with a maximum of 10 FC during use, as opposed to a typical room that requires 20-70 FC during normal non-AR use. This allows the AR overlay to be visible at surface with the maximum visibility. VR escapes this through the use of head mounted displays that encase the user’s vision in a controlled blackout environment.

Interiors in dedicated AR spaces have requirements as well. Depending on the sophistication of the technology, it may require fixed objects within the room to lock onto where the AR visual field sits. This is similar to VR headsets, such as Oculus Rift, which need to calibrate their sensors to know where your HMD is in space in order to position the experience at the right location in the visual field. Walls should be neutral mid-value in color with contrasting dark ceilings and floor materials. Avoid textures, sheen, and patterns on walls and fabric, as these can degrade the image of the AR overlay.

The computing power required for many of these system is much greater than for standard applications. Poor or limited bandwidth will hamper the experience and can cause latency issues or crashes. The rule of thumb when working with this technology is that you should double the expected bandwidth required whenever possible.

Following these best practices can put your design project on a good path for success. I recommend starting off with unique aspects within a smaller project’s total design project so you can acclimate to the process, and get a feel for how it will be beneficial. Doing this on multiple projects will allow you to build your skills and improve your design portfolio across greater platforms. Happy designing!

This is reprinted with permission of the DRL Group. It originally appeared here. Raymond

Kent is the Director of the Innovative Technology Design Group and a principal with DLR Group/Westlake Reed Leskosky specializing in technology systems for the performing and cultural arts, healthcare, Government, higher education and corporate markets.

He is a co-author of the STEP rating system and has served as the chair of the Technology Task Force for the STEP Foundation. Raymond received the 2012 InfoComm Sustainable Technology Award and is involved with the Center for Sustainable Practice

in the Arts and can be often seen presenting at major conferences on sustainability and technology.

Raymond

Kent is the Director of the Innovative Technology Design Group and a principal with DLR Group/Westlake Reed Leskosky specializing in technology systems for the performing and cultural arts, healthcare, Government, higher education and corporate markets.

He is a co-author of the STEP rating system and has served as the chair of the Technology Task Force for the STEP Foundation. Raymond received the 2012 InfoComm Sustainable Technology Award and is involved with the Center for Sustainable Practice

in the Arts and can be often seen presenting at major conferences on sustainability and technology.

supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

.png?sfvrsn=388eb01d_1)

.png?sfvrsn=43e47a15_1)