Bring Back the Buttons

Watch any front-of-house mixer and you’ll see it. There is a mystical confidence in the way they make adjustments. Scarcely looking down from the stage, moving hands along the channel strip, they find the controls to conjure exactly what they want to hear.

The moves come with experience and repetition, building up the automatic habits of muscle memory. And with that ease comes a certain pride in operating almost by sense alone. The same long-cultivated expertise can be seen across any number of tasks in the AV universe. Anywhere a physical task or tactile control interface is in use, the operation gains the ease of instinct.

But that’s changing with the loss of tactile interfaces in favor of capacitive touchscreens. This progress seems inevitable, but there is a school of thought advocating for more careful consideration before we eliminate all buttons, switches, and potentiometers in favor of some more “modern” interface.

Amber Case

Amber Case

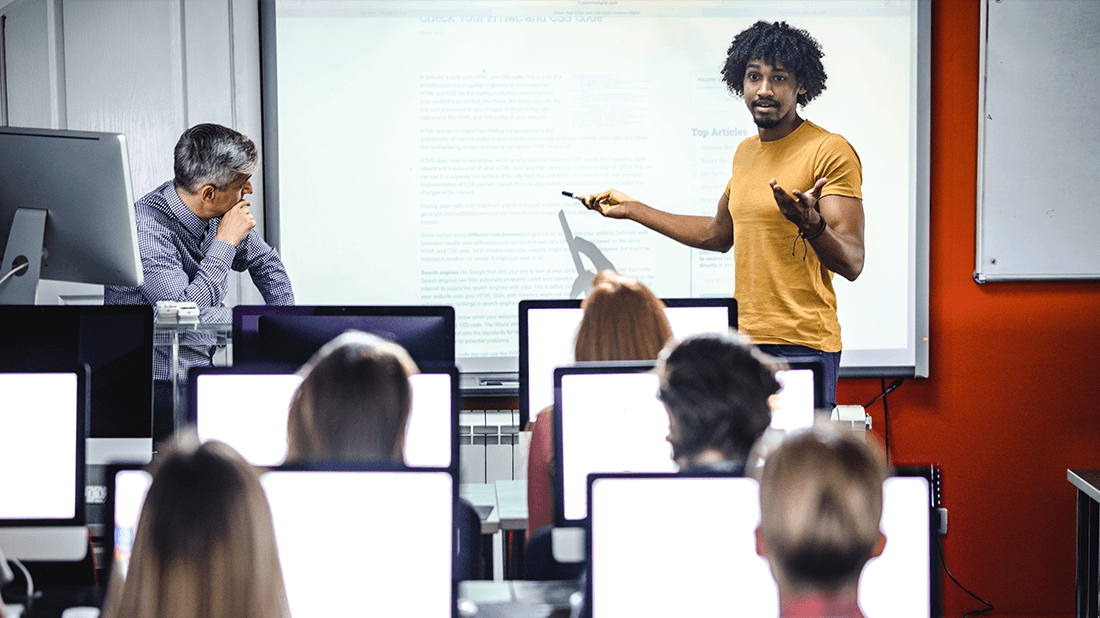

Advocates of “Calm Technology,” a set of experience design principles originally conceived by human-centric engineers at Xerox PARC in the 1990s, feel that the time has come to reclaim some of the vast amounts of attention our technology now demands from us. With us living in the “age of ubiquitous computing” that Calm Tech’s originators speculated about, their ideals are being passionately propagated by Amber Case, a technologist, speaker, author and research fellow with the Institute for the Future.

Case shared her ideas about how we can take back a bit of control and pride in the operation of technology in a dialogue with Douglas Rushkoff, another tech-philosopher and author of Team Human, at Betaworks Studios in New York City. Their topic was “Taming Technology to Serve Humans,” but the message was the opposite of what you’d expect.

It wasn’t about using more data and analytics to provide ever more notifications and updates from countless apps. It was about getting calm, getting methodical, and getting back to what those audio engineers already know. Buttons and toggle switches are pretty great. And sometimes all you need is a subtle cue from a blinking light to indicate status.

As those who have switched to an iPad EQ from a fader-based option may attest, with the loss of that familiar tactile slide, or the reassuring clicks in a sequence of button pushes, comes an increase in the amount of attention we are involuntarily required to spend interacting with technology.

It seems that somewhere along the path to making everything “user-friendly,” we forgot that humans often find it easier to operate via the use of muscle memory. Now instead of the simplicity of a light switch, which only asks for our peripheral attention to perform a function, screen-based interfaces usually demand our full attention so we can locate a simulated button and launch a command.

Calm Technology

Calm Technology

Case has written a book and created a series of Calm Technology exercises that may be helpful reminders of some of AV design’s most vital attributes. Some will sound familiar, as they are ideals that are also core to systems integration: “Technology should work even when it fails” (i.e., create a redundant operating scheme to continue use even when pieces of a system break). And related to our most central function in developing communications systems: “Technology should inform and create calm.”

But Calm Technology also provides a helpful reminder as we continue along the path of less hardware, more software: “The right amount of technology is the minimum needed to solve the problem.” This prompts something to consider when a client asks for an app: How many swipes and screens do you have to go through to get something done? Can a simple switch or button do the same job?

We’ve all heard that there is a craving for more tactile experiences. And in fact, there is a design trend toward fashionable new light switches that look like they were crafted in the 1930s, but in fact they offer all the fancy networked multifunctionality of the modern age.

It’s time to think about where it might make sense to bring back buttons. As Case points out, the founding thinkers behind Calm Technology predicted that in this time of ubiquitous computing, the scarcest resource is our attention. So why squander our attention on screens and excessive alerts? Why not get back to using our peripheral attention to quietly monitor situations, engaging more senses to notify users of changes in status. Remember the button and think about the best way to bring muscle memory back.